Today’s guest is a writer, director, producer, actor, and indie filmmaking legend, Edward Burns.

Many of you might have heard of the Sundance Film Festival-winning film called The Brothers McMullen, his iconic first film that tells the story of three Irish Catholic brothers from Long Island who struggle to deal with love, marriage, and infidelity. His Cinderella story of making the film, getting into Sundance, and launching his career is the stuff of legend.

The Brothers McMullen was sold to Fox Searchlight and went on to make over $10 million at the box office on a $27,000 budget, making it one of the most successful indie films of the decade.

Ed went off to star in huge films like Saving Private Ryan for Steven Spielberg and direct studio films like the box office hit She’s The One. The films about the love life of two brothers, Mickey and Francis, interconnect as Francis cheats on his wife with Mickey’s ex-girlfriend, while Mickey impulsively marries a stranger.

Even after his mainstream success as an actor, writer, and director he still never forgot his indie roots. He continued to quietly produce completely independent feature films on really low budgets. How low, how about $9000. As with any smart filmmaker, Ed has continued to not only produce films but to consider new methods of getting his projects to the world.

In 2007, he teamed up with Apple iTunes to release an exclusive film Purple Violets. It was a sign of the times that the director was branching out to new methods of release for his projects.

In addition, he also continued to release works with his signature tried-and-true method of filmmaking. Using a very small $25,000 budget and a lot of resourcefulness, Burns created Nice Guy Johnny in 2010.

The film debuted at the Tribeca Film Festival. While he was releasing that film, Burns wrote, starred, and directed Newlyweds. He filmed this on a small Canon 5D camera in only 12 days and on a budget of only $9,000.

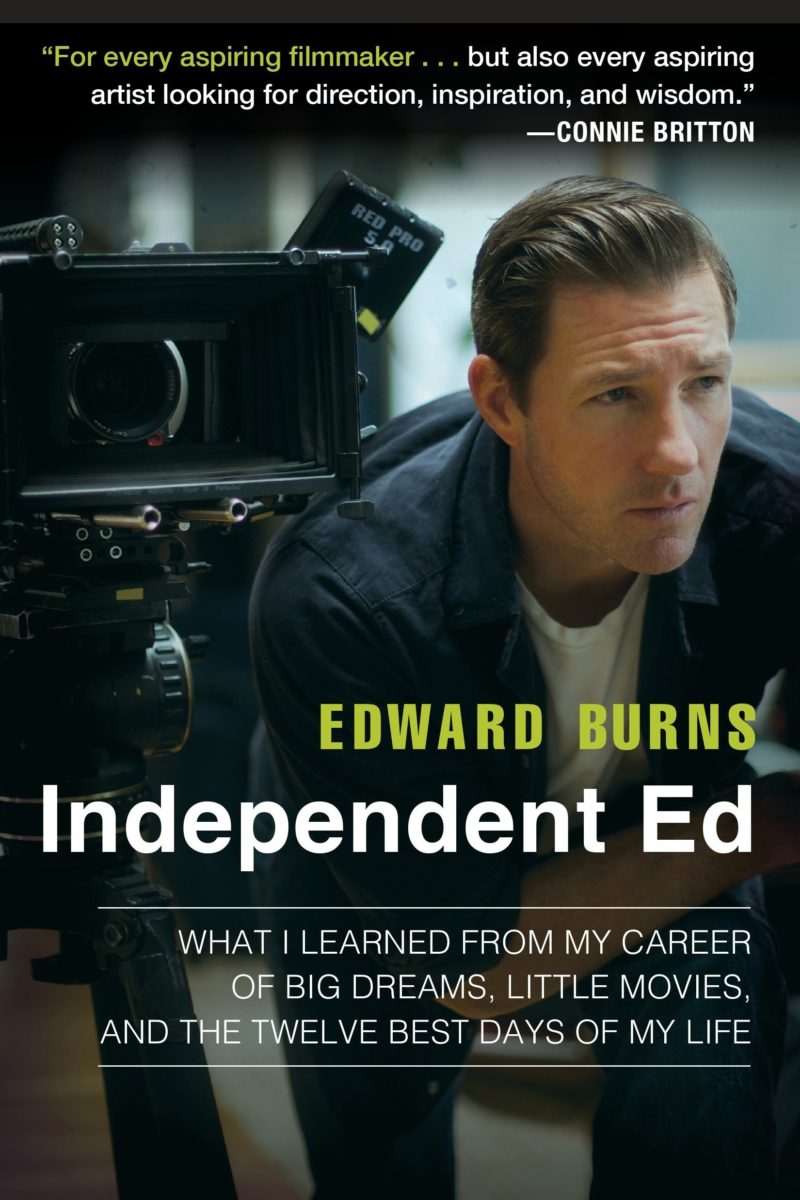

In his book, Independent Ed: Inside a Career of Big Dreams, Little Movies, and the Twelve Best Days of My Life(which I recommend ALL filmmakers read), Ed mentions some rules he dubbed “McMullen 2.0” which were basically a set of rules for independent filmmakers to shoot by.

- Actors would have to work for virtually nothing.

- The film should take no longer than 12 days to film and get into the can

- Don’t shoot with any more than a three-man crew

- Actor’s use their own clothes

- Actors do their own hair and make-up

- Ask and beg for any locations

- Use the resources you have at your disposal

Ed has continued to have an amazing career directing films like The Fitzgerald Family Christmas, The Groomsmen, Looking for Kitty, Ash Wednesday, Sidewalks of New York, No Looking Back, and many more.

Ed jumped into television with the Spielberg-produced TNT drama Public Morals, where he wrote, directed, and starred in every episode.

Set in the early 1960s in New York City’s Public Morals Division, where cops walk the line between morality and criminality as the temptations that come from dealing with all kinds of vice can get the better of them.

His latest project is EPIX’s Bridge and Tunnel is a dramedy series set in 1980 that revolves around a group of recent college grads setting out to pursue their dreams in Manhattan while still clinging to the familiarity of their working-class Long Island hometown. He also pulls writing, producing, and directing duties for all the episodes.

Please enjoy my conversation with Edward Burns.

Right-click here to download the MP3

Listen to more great episodes at Next Level Soul Podcast

Follow Along with the Transcript – Episode 135

Edward Burns 0:00

Do you have to trust your gut like know when it doesn't work and when it's not funny or adjusted you know, it feels whatever your gut is telling you that and a lot of times you just you know you're afraid to make that kind of change.

Alex Ferrari 0:27

I've been able to partner with Mindvalley to present you guys FREE Masterclass is between 60 and 90 minutes, covering Mind Body Soul Relationships and Conscious Entrepreneurship, taught by spiritual masters, yogi's spiritual thought leaders and best selling authors. Just head over to nextlevelsoul.com/free

I like to welcome to the show Edward Burns man how you doing Ed?

Edward Burns 1:04

Oh, it's been great to speak to you.

Alex Ferrari 1:07

I've been a fan of yours, man since since Brothers McMullen days, you are one of those lottery ticket stories, those kinds of Cinderella stories that you hear about from the 90s You know, along with Robert and Kevin and, and Richard Linklater, and all those guys that came around and you came in that crop man of like, I always tell people, the 90s was just like such a glorious time to be a filmmaker, because it's felt like almost every month, or every week, almost that was one of the stories that came out. Is that fair? To say?

Edward Burns 1:38

No. Probably it probably wasn't mean, I know. For me, it certainly was, you know, Sundance was the launching pad. Every year, you know, you would see those articles coming out of there. For me, it was there was a couple of movies. You know, obviously, Rodriguez is El Mariachi. But I think before that, Nick Gomez had a movie called laws of gravity made for 23,000. And that was really a huge influence on me. When I could see like, oh, wait, you can make a feature film for 20 grand all in. And it can then get picked up for distribution. Because really prior to that, what you would hear when you were in film school, and I'm in film school, and like 8990 91 Is that the way in is to make a short film. Remember, there was there used to be something called the IFP used to run something called the independent feature film market down at the Angelika theater in the village. And that's where you know, you could get your short film in there, you know, all of the buyers and managers and agents, the whole like New York indie film scene would be there. And that was the launching pad. And I remember I went there with my first short film. And there were short films that had like big budgets that, you know, really high end production value, and I knew I would never be able to raise enough money to compete with that. Then when laws of gravity comes out, the living end, the Gregor Rocky movie came out.

Alex Ferrari 3:14

Yes, right. And the one movie that always gets, he doesn't get the credit that he deserves Robert Townsend Hollywood shuffle. Oh, without a doubt that one was a little bit. That was but that was he was still but it was still like he put it on his credit cards, though. And it was Robert it was 8687. And he was in LA and he made it for like it was in the 20 to 75 range. It wasn't Yeah, it wasn't it wasn't crazy. He put it on credit cards. He was the first filmmaker that I heard of that put on his credit cards because I was working at a video store back in the late 80s, early 90s. So I remember Hollywood shuffle and it was just

Edward Burns 3:51

One year he's not doing that kind of 87 87 Okay, yeah, so that's a little earlier.

Alex Ferrari 3:56

It's right before it's before sexualize hits you know, which was a million dollar but before he launched the Sundance and and before laws of gravity and mariachi and clerks and all that run but he was one of the first to do it but he doesn't get in the he's never in the same conversations and I always make it a point to point out how instrumental Robert Robert Johnson

Edward Burns 4:16

Yes interesting yeah, I like So when would metropolitan if that is that that metropolitan is probably

Alex Ferrari 4:23

But that's what you That's right. What's that? What's what's what's once metropolitan Andrew Stillman movie. That was another one. That's right. That's right. That was around. Oh, god, that was that was around that time. But also like, I mean, the ones that got the most attention. I mean, obviously Robert got the biggest. I mean, Robert Rodriguez got the biggest thing with mariachi like he. That was that's still a mythical in in the halls of independent film. People still talk about El Mariachi as this mythical thing. And in the same breath with clerks and Brothers McMullen. Then slacker as well.

Edward Burns 5:03

There's probably two years before me that was another big one. Because I think Rick made that for maybe in that 25 to 50 range,

Alex Ferrari 5:11

Right! And I was just had Scott Moser on the show. And Scott was telling me I'm like, Scott, what was the who was the thing? He's like, Oh, is slack or slack was the blueprint? Because I'm like, You guys didn't have a blueprint? Really?

Edward Burns 5:21

It was like before that though, you know, Long Island zone. How Hartley Yes, the guy who? Who I feel like because he did three in the early 90s, you know, he did. It was the unbelievable truth. Simple min, and I forget the third. But those were all done, you know, in that under $100,000 budget range. And the thing that was interesting, back to sort of the whole, you know, short film versus a feature was seeing that every year, all of a sudden, you know, you had Hal Hartley then you mentioned Rodriguez,

Alex Ferrari 6:00

You had don't forget Jim Jarmusch. Jim Jarmusch,

Edward Burns 6:04

But that's prior Yeah. He's more in the Spike Lee,

Alex Ferrari 6:08

She's gotta have it. Yeah, she's gotta have a time, right? You know, those

Edward Burns 6:10

Guys came up mid 80s. This is more of that early 90s micro budget, that then got distribution. And now it was really, I think the thing that changed things, because it wasn't just make a short as a calling card to get an agent to hopefully make a Hollywood feature, right? More like, more like an indie rock band, who is like, you know, hey, we're gonna just put out our own thing. And this thing has its own value. We're not trying to parlay this into a gig to work with the studio, we're gonna create something new here that then we can build upon. So that is really what changed, I think, in the early 90s. You know, if you look at Kevin Smith, you know, credit, you know, clerks is a micro budget movie, but he basically stays within that milieu. You know, I know I did, as well, how Hartley's another guy who did some guys or gals chose to sort of take that and turn it into sort of a bigger sort of more studio type of filmmaking career. And that's sort of I think that's what folks we're trying to do, like, treat it more like you're in a band. And it's like, are we make gritty sort of punk rock albums. And that's what we want to continue to do.

Alex Ferrari 7:24

So when you you know, when you were coming up? I mean, I mean, this, your story also is also quite mythical about the whole being a PA and, and working at ET, can you tell everybody because a lot of people listening might not know the story of actually how you got? Well, before we get how you got to Sundance, how did you get Brothers McMullen off the ground? We're like, what made you think the lay you can make it? I mean, I mean, it was it's nuts. It's like, now you look at it, you're like, Oh, well, everyone could do that. But back then there was just no internet. There was no knowledge about this, really. So how did you do it, man?

Edward Burns 8:00

Um, I mean, it's a crazy long story. And you just tell me to switch gears when you're trying to remember because it's like I make the film 28 years ago when I am. Basically I start when I'm 24. I think. So. Coming out of film school, like you said, I'm a production assistant at a television show in New York, which basically, my job was driving the van and setting up the lights. That's the extent of what I did. So I had plenty of time. It was a job that required no mental focus at all. So I spent all my time writing screenplays. i At the time, you know, one of the guys we forgot to mention is Tarantino and reservoir. Well, there's that guy. So I see Reservoir Dogs. And I'm like, Okay, that is what I need to write. So I probably write in my four years, or three and a half years out of homeschool, five feature length scripts. Three of them are reservoir dog rip offs. I am poring through the trades every day, trying to find or identify the agents or managers who sign first time screenwriters. So that's why I'm sending all of my scripts. Smile, right? And every day, my dad told me somebody's like, look, there's absolutely another filmmaker out there who is outworking you. So you need to make sure every day you do one little thing to chip away at the brick wall that separates you from the dream. So that meant you know, I'm going to write a scene in my script, or I'm going to write another letter to an agent, or I'm going to send my short film into another film festival every day I made sure I did one little thing. So I write all these scripts. I send them out. I get nothing but rejection letters back. And I come to the conclusion and this has happened to me a couple times in my career, or kind of recognize, well, maybe I'm just not that good. You may be It isn't that they don't, they can't recognize what a talent I have. Maybe I'm just actually not ready to go back to school and learn a little bit, right? And at the time, I see an ad for the Robert McKee story structure class. So a lot of people might poopoo that no, you know, traditional Hollywood structure is BS, you know, free X don't pay any attention to that. For me, it was it was incredible. I go there and and you know, you learn a lot of this stuff and you're you know, screenwriting one on one stuff in film school, but again, you know, a lot of it you forget or, you know, if you want to be like a cool rd, kind of kid, you're dismissive of that stuff. This point, after five rejected screenplays, I am no longer thinking I'm hot shit, I am not dismissive of anything I recognize, I need to learn. Right. So I take the class and you know, a couple of things that he said, that really struck a chord with me one was, what is your favorite genre of film? What do you like love to watch? That is the next screenplay that you should be writing. You know, like, our write a horror script, like, you know, I actually do that. And at the time, I was like a massive Truffaut and Woody Allen. Like, that's all I was doing. I was always watching. So I was like, okay, that's what I'm gonna do, basically, relationship, comedy drama, a little bit of an ensemble. You know, I look at those Woody Allen films. And I'm like, Okay, that's a winner. You know, for people on everyone listening to you, I think those were words, but one shot without a cut, that lasts almost two minutes of two people walking down the street in Manhattan, talking about their relationships. Okay, I know from my, my film school days, that's about as easy as you can do with no money. That says, As easy as seen as you can pull off compared to shooting, let's say, an interior scene in a crowded restaurant, where I'm going to need to hire extras and whatever. So as I sit down as and when I leave McKee, I'm like, I that's what I'm going to do. I know that's the genre that I want to play. And I decided to make an ensemble, because I knew from my, my student films, when you're not paying your actors, there's no guarantee that any of them are ever going to show up. You know, especially in New York, everybody's got other jobs, they're waiting tables, they're working in a gym, you know, you would have people just bail on you in the middle of the shoot. So I said, if I have an ensemble, and I cast myself and my girlfriend opposite me, I know that even if this thing blows up, I have a short film. And that's why it's a crazy way to write a screenplay. But I wrote it as for sort of different movies. The first movie was the three. And then I listed all the locations that I knew I could get for free. So I knew I could get my parents house. So that was location number one, then I knew every street corner and sidewalk and public park in New York City. I knew from my working in news days, you did not. First of all, there was no cost to shoot there. And you would never be bothered. No cop would ever ask him certainly in the early 90s in New York, if you had a permit to shoot. Now, when New York was still a little greedy, then they could care less about three students out with a camera, right? I was like, so that's what the movie will be. I'll have these three brothers. And the one movie is the movie that takes place in their house. And then they'll each have a girlfriend in Manhattan. And those will be my other three short films. So I kept thinking if it didn't work out, I could have a 25 minute movie 50 minute movie 75 minute movie or

Alex Ferrari 13:45

So you've actually backed into, like you backed into this film, with disaster in mind, like, reverse engineered the whole thing. It's amazing. That's remark I had never heard that part of the of the myth, if you will.

Edward Burns 13:58

That's kind of how I laid out the script. And, um, you know, so then there was an article in the AFPs old magazine, the independent, and they did an article on living in laws of gravity. And I forget the maybe one of the HAL Hartley movies, and they basically broke down those budgets. And they were like I said earlier, one was 23. One was 28. One was like 35. And I looked at that, and I said, based on my experiences with my student films, I was like, I think I can pull this McMillan's grip off for about 25,000 I think I get it in the camp of 25. So my own land, you know, get my dad was a cop in New York. I had a working class kid grew up with no money, no connections in the business. We knew a lawyer and convinced this guy to put together a limited partnership, and we were going to sell five $5,000 shares to get the 25 Grand. He knew a guy who works on Wall Street. That guy gave him five grand And that's all we raised. Yeah. So basically, we raised $5,000, I convinced my dad to give me about another four. And I basically tell him in this guy with the nine, let me just go and shoot together, sort of a sizzle reel a trailer, and we'll use that to raise more money. But I knew that I was going to try and shoot the entire film for $9,000. That was my goal. So I set out I put an ad in Backstage magazine that basically says, you know, no budget in the nonunion no pay, but we'll feed you. It's New York City. So I probably got 2500 headshots, through all the headshots. And then there's some, you know, great stories about, you know, how I was able to get some of these actors. But you know, the part of Molly, the older brother's wife, probably auditioned 1520 actresses, and I'm thinking to myself, the script is terrible, because the scenes that these young actresses really just weren't playing. And then Connie Britton came in one day, sitting behind the camera, shooting her audition, like, Oh, my God, this kid is good. Wow, maybe the scenes aren't so terrible. So Connie ends up being cast in the movie. And throughout the production, Connie was kind of like our you know, she was our rear, we just knew like, okay, she's like, really the super talented one here. You know, when you're acting opposite her, you better bring your A game. And so so we get Connie in the movie, the other actors are all unlike Connie, nobody had ever been on a set before. Nobody had ever been in front of a camera before. And I set out to go make this film. We probably shot about six days, over the course of maybe three weeks. And then I kind of run out of money. But I don't let the cast know that. And what I did, do, we ended up shooting 12 days over the course of eight months. And what I would do is I would save up some money from work and hit my dad up for a little bit of money. A camera guy was working with Dick Fisher would say hey, look, I'm not working to Saturday and Sunday, and I have the camera, buddy of mine is available to do sound. Who can you get from the cast that's available? And you know, I would then go all right, Jack and Mike are available. Let me see what scenes are still not shot for it. And then the other crazy thing I did was, it was you know, we shot 16 millimeter, right? We couldn't afford to buy any new cans of film.

Alex Ferrari 17:49

So short ends, short ends. And 60 not even super 16. But 16 short ends use like leftover stuff from industrials.

Edward Burns 17:57

So, so it was cheaper for me to re enroll in Hunter College for one class, which I think was probably I don't know, at the time, probably 300 bucks. So I can get a student ID because for the short ends with your student ID was something like 25% off or something like that. So I reroll in school or you get the cheaper price on the short ends. But then of course when we can afford to develop anything until we're done shooting. So eight months after we get these 12 days done, we develop stuff and then you know from short ends, a lot of times some of that, that film has already been exposed. So it made the editing a little bit easier when you do like okay, well we're cutting that scene because we just don't have that scene.

Alex Ferrari 18:46

So anyway, so you had eight months that you had a bunch of film reels in your, in your in your apartment.

Edward Burns 18:53

After those first six days. We're just you know, Dick says, Hey, I'm free on this day. I say great. I go buy some film stock. I call the actors. I come up with the scenes, we go shoot those two days, and then it's like, alright, what are we gonna shoot again? I have no idea.

Alex Ferrari 19:09

But So how long were you with the movie in the can before you gotta developed?

Edward Burns 19:16

Alright, so after we once we finish shooting, we had everything at that point. Then I go to the do art film labs, and it was a great guy random place named Dick young, Bob Smith. Those are the two guys who ran and to their credit. Excuse me. They were real supportive supporters of indie film and young folks in New York trying to make it happen. So you know, my dad went down with me there and explained to them hey holdouts for Eddie. But, you know, he's got this film. Here's all the film. We'd love to get it processed can pay for it all now. But if you can defer those costs will slowly paid off over time. And they were generous, generous.

Alex Ferrari 19:58

So like, almost like layaway. A payment plan for for development that that world does not exist now you have to find some some very special people.

Edward Burns 20:07

I mean, could you imagine though, trying to shoot an indie film on 60 millimeter today on short ends, like, that's why, for me and I've heard you talk about it as well. It is so exciting right now if you're a young filmmaker that you can pick up this friggin thing, your phone and go and make a feature that's going to look 100 times better than Brothers McMullen. Look, you know, he

Alex Ferrari 20:30

The lenses you can get the cameras you get. I mean, I shot a whole feature on a little pocket camera, and just got vintage lenses and just went out and shot a movie in four days in a war. And I got it just it looks stunning projected at the Chinese Theater on a 2k up res stunning, most beautiful thing I've ever shot and I've shot things with much bigger budgets. And I was just this little tentative p camera it was just gorgeous. So and now there's like four 6k cameras in like the little pockets. And it's just it's ridiculous. It's ridiculous. So yeah, so you got got everything developed on layaway. Fucking great story, a layaway, then you're editing it, I'm assuming what this is

Edward Burns 21:11

Even crazier. So we have to beta because I work in

Alex Ferrari 21:17

Beta but of course,

Edward Burns 21:18

And they cut the show on beta. So what me and Dick would do is at the end of the night, like if we had a movie premiere, let's say because we covered those things. We were the last people in the office, we'd leave the side door of the office open, you'll be left. Well next door to the Mayflower Hotel, have a drink, come back into the building at midnight, and then edit till five in the morning using their editing bays.

Alex Ferrari 21:45

And without without permission. So always ask for forgiveness, never for permission.

Edward Burns 21:51

Exactly. So we do that we cut the movie together, you transfer everything to beta.

Alex Ferrari 21:54

Because I used to cut on tape as well on beta SB. Is there a film print of this? That's not a transfer from Vidya? Did you ever go back to the neg on anything? Yeah, eventually did okay. But first, you just cut together a video edit of that. Yeah, did you call it great, you did color grade that now there's no color grade, whatever it was, it was

Edward Burns 22:17

Whatever it was, it was no sound mix. Nothing. Other than, you know, we basically, at the time, we just borrowed all of this traditional Irish folk music from this musician named Seamus Egan. And I'll tell you the story of like the great ending that happened for Seamus but at the time, you know, I couldn't afford a composer. And I thought I will just use needle drops from this guy. And he was a friend of a friend of a friend. So I knew that I could get to him eventually. But at the time, I was like, I need music for the film. I have no idea what's going to happen with this movie. I'm really, when I make the film, certainly you have the dream that maybe it'll get picked up for distribution. But as I said earlier, you know, for five years, I'm sending out my scripts, I can't get even a phone call back from an agent. I'm hoping the film will be something of a calling card, and then maybe nothing else will go to the festival. Someone will see it and I'll get an agent. So we cut the film transferred to VHS at the time, it's two hours long. We're both exhausted. I mean, I know it's still a rough cut. But you know, it's your first film, it's your baby. I don't know what seems to cut. So I knock off a bunch of you know, VHS copies of it. And then I start the process of doing the same thing. I'm poring through the trades, who are the agents who are signing first time filmmakers. What are the film festivals where do the production companies and the distribution companies send it out everywhere film festivals, a year's worth of rejections? And then the you know, the famous story is the Redford Sundance story. Right. So you know, I'm working in Entertainment Tonight. Redford is there to do press for I believe it was quiz show. I I know that you know obviously Redford Sundance I take one of these rough cuts with me. And I have my little you know 32nd Spiel rehearsed so that when he gets up with his PR person, and usually you shoot these junkets in a in a big hotel, so I know he's gonna go out the main room, I'll go out the second bedroom, cut him off as he's getting into the elevator, give him the spiel, hand him the tape, and we'll see what happens. So that's exactly what I do. And he listens to me and he says, oh, okay, great. Well, we'll have someone take a look at it. And he hands it to his PR person and the elevators door, the elevator doors close. And that's it. And I think well, I guess, you know, I was kind of hoping he would want me to jump in the elevator and hear more about it.

Alex Ferrari 24:58

And just to take the point ever playing to his house? And then you know, all that stuff, of course, of course.

Edward Burns 25:05

Doesn't work that way. But two months later, I'm at work. And I get a phone call from Jeff Gilmore, who was the programmer at Sundance at the time. And just as Hey, Eddie, so worried we got this movie here. It says it's a rough cut. Just want to know if you've finished it. I lie I say yes, of course I did. He says, so it says a rough cut two hours. What's the running time now? I say 95 minutes. Because, you know, the topo films, Woody Allen films are overwhelmingly you know, now you know, under. And this is what, what scenes Did you cut. And by this point, now, the movie is a year old. So I've kind of seen it and unless in love with it. So there's a handful of scenes I know, I want to cut. And then I just riff and named some other scenes. And he says, You know what, actually, that sounds pretty good. Alright, we'll be in touch. Two weeks later, they call up and they say you're in. So now that's probably September.

Alex Ferrari 26:00

So hold on a second, when you get that call? What is that? I mean, like,

Edward Burns 26:04

The office, and all of the guys that I work with, you know, the crew guys, they will work on the movie, you know, like, they will have done sound for me. Like they know, you know what we're doing with the editing machines. So definitely high fives and everybody's cheering and like, I can't believe that Holy shit.

Alex Ferrari 26:23

Or little Eddie our little eddie he made good he's gonna get he's gonna go to the show.

Edward Burns 26:28

That's exactly exactly what it was. So, so now though, I have to raise another 25 grand at a minimum to finish the film. You know, because print on beta. So I gotta go back to the negative recut it right. Because yeah, and blow it up to 35. And, you know, I've never done that before. I don't know how to do that, you know, my student films that that I made. I cut myself on a little like movie Ola slicer, you know, we had to sync up your your your mag sound to your picture and tape it together. I was like, I can't do that for a 95 minute long movie. So I can't remember exactly how but I'm put in touch with Ted hope and James Seamus a good machine. And those are the guys who really, you know, quite honestly, at that time, took me under their wing. They came on as producers. And they helped me, you know, not only they taught me how to finish a film, but Ted was really invaluable in the editing room with me. You know, I knew I knew 20 minutes I could cut out of the movie like that. But that last 10 was tough. And he gave me two great bits of advice. Because I'm telling you, you don't need the scene and the scene is so great. Use it in another one of your films. He loves. Needless to say, the scene has never so good that you end up revisiting it wasn't. Everything he said is how many times if he walked out a movie and said that was pretty good movie. But that was that 20 minutes in the middle. It was a little weird kind of drag there. Because nobody ever walks out of the theater and says God, who was a movie was really good movie was too short. He's like, I'm telling you, let's get this thing down to 95. You got a nice pre breezy comedy year puts a smile on your face, like, get people in and out. And I'm telling you that you enjoy. And it was I mean, it was great, great advice. And that's what we did. So then the interesting thing was because we were up against the deadline for Sundance, and I might have the dates exactly wrong. But I had to fly to Sundance for the start of the festival. And I don't know if they still do it, but they would have like a filmmaker orientation and what you did with all the filmmakers those first couple of days. And our first screening is until four days after that Ted has to stay in New York because like he has to wait for the blow up to happen. So do our blow up, Ted grabs it that day, goes to the airport gets on the plane flies to Sundance we screened the next morning at the Egyptians, so I never even get to see the film projected to

Alex Ferrari 29:08

Jesus Christ. And then and then as As the legend goes, then there's there's was there a bidding war for it? How would that go anymore?

Edward Burns 29:18

We Tom Rachman at Fox Searchlight you know which was a brand new company with Moen was the first movie they ever released. He he was at the first grading and again the funny thing is, so they tell us like and maybe it was because of the Redford thing like there were 80 movies in we were the 19 so even on my flight to Park City, there was like an article listing all the movies and competition we weren't even mentioned. So we will little bit of the also ran so you can imagine that.

Alex Ferrari 29:53

That feeling is like it's are we are we there is because you just can't pick up Bob and call Bob at this point.

Edward Burns 30:01

The beginning pick up a phone to do anything like that. So anyhow, you know, so we had a good crowd at the festival, I, again to my memory, we did not have many buyers there other than search like, and at that screening, you know, it's pretty great. It's like the reaction is great. I got to meet a lot of people and a bunch of agents and managers and afterwards they given you their business cards. Like we got to do lunch and all that. But you know, Rothman was there. And that night, over dinner before even our second screening, we sold the movie to Starbucks.

Alex Ferrari 30:38

And what they feel me asking what was the final sales for

Edward Burns 30:41

We sold it for 250.

Alex Ferrari 30:44

Jeez you must have been ecstatic.

Edward Burns 30:46

We were through the roof. I mean, we could not believe that cheese. And we had some box office bumps built into that. Um, that would have gotten us to a half million if the movie basically doubled clerks is domestic box office. And I think courts at the time did 1.2 or something like that. here that the movie would do 2 million, they thought was an absurd notion. And you'll never get there.

Alex Ferrari 31:17

I mean, yeah, there's no stars in it. It still was 27,000.

Edward Burns 31:22

Movies did none of those little ones that we talked about, you know, they would do 400 50 600

Alex Ferrari 31:27

Mariachi mariachi I think mariachi with Columbia Pictures pushing it into put a million dollars in remastering, it still only pulled him like a couple mil like two or 3 million theatrically if I remember correctly, so it wasn't like it was a blockbuster. Yeah, but yours.

Edward Burns 31:45

American, you know, it ends up doing $10 million. Which was just, you know, just nuts. But the, you know, it's talking about the guy's a good machine. And the other great bit of advice was from James, Seamus. And he was like, look at when you're at the festival, who knows if we're going to sell the movie, but I'm telling you like those 10 days, you will never be harder. Like there's a feeding frenzy that happens at the festival. And you know, when we see it every year, you know, these movies that sell for a ton of money at the festival that you know whether they want or not, who cares? Like filmmakers are getting paid. That's a good thing. But he's like, You better have another screenplay in your hand because they will ask you, what do you want to do next? And if you can hand them a script and say I'm doing this Next, you'll get that thing greenlit in a hurry. So I quickly wrote basically what I thought was a funnier version of Brothers McMullen. Because we didn't really think we would sell brothers MC mama. So that movie was she's the one and you know, grew up and basically said, what Seamus said he was gonna say, What do you want to do next? I said, I want to do this. Here's the script. She's the one. And within a week that was greenlit. So you know, I go out to LA for the first time in my life as a guy who sold a movie to Fox Searchlight. And now I've got my second film greenlit with a $3 million budget.

Alex Ferrari 33:08

And that is the, again, the lottery ticket. That is absolutely the lottery ticket. And I constantly if you've heard the podcast, you know, I've talked about it so many times that filmmakers think that that is that's the that's the plan like no do that. It's not the plan. Eddie, he did not plan you didn't plan any of this. It just you were just like, dude, if I get an agent out of this, I'll be ecstatic.

Edward Burns 33:33

You know, my my producing partner Aaron Lubin interview who you got to, you know, he talks about it as the bullseye. You know, when we're making our micro budget movies, you know, we're always talking about like, the Bullseye is not a business plan. You know what I mean? Just because, you know, the big sick, for example, a more recent movie that went on to do really great businesses in indie film work, doesn't mean you know, your film, my film, anyone's home was going to do that business like that is the bullseye, you've got to come up with that's why I like I love your book, when you talk about identifying the niche audience that you've got to find and really thinking about back then, you did not need to think about the audience in the same way, because there were so few indie movies being made. I mean, there's still there were hundreds, but it's not like today.

Alex Ferrari 34:28

Now that's 100 a day, ya know, it's instant. I trust me. I know, I talk to these guys every day. I talk to filmmakers all the time. And I'm seeing it because the the best in the world the best. The good news is, anyone can make a feature film. The bad news is anyone can make a feature film. It's it's it's there's a gluttony of product and put

Edward Burns 34:47

Yeah, and that's, and you know, I mean, I've spoken to film schools and film classes over the years and people bring that up and why should I do too many films and is it you know, now that there's no barrier to entry? You know, I'm like, hey, what's the difference? Now? It's It's the equivalent of a kid who can pick up an acoustic guitar and just start writing songs, right? And he can throw them on to his, you know, however you would, you know, on your GarageBand on your laptop, what's the harm in that? Like, you know, you can make a movie for a couple of 1000 bucks now, why discourage anybody from doing that? Because what may end up happening is someone is going to create that movie. That is the equivalent to you know, Bob Dylan kind of reinventing sort of, you know, folk music or rock and roll in the mid 60s, you know, there will be a version of the Ramones that come from the indie film scene, and someone who kind of just was like, Hey, I only got five grand, I'm gonna make this little movie.

Alex Ferrari 35:45

And, and I think the best the best advice I've ever heard about that, because you know, you're right, you're absolutely right. But it's about finding that voice that thing that makes you special like brothers with Bolin was spawned from you today. That's just just such your that's, that's definitely something in your wheelhouse from your personal experience and meant something to you. Like, I can't write Brothers McMullen. I would write it based on stuff I've seen. It's not something I experienced. But like my last movie, I shot ego and desire, which is about filmmakers trying to sell their movie at Sundance, I can talk about that very clearly. And I can talk about the pain and the suffering of filmmakers go because that is something that's really in my purse, but that's my voice. And that's what filmmakers think today. They're like, Oh, I'm going to make a Brothers McMullen. Or I'm going to make a mariachi or I'm going to make a Reservoir Dogs, like no man, you failed from the moment you started, you got to do something that is really true to your own voice. Because that's the only kind of secret sauce we've got right? To stand out.

Edward Burns 36:46

No, that's absolutely true. And you know, I mean, I've told people like this, you know, I mean, as you said, I am one of the lucky ones, right? I got the lottery ticket. And it is still after 25 years, and it was hard after three years. You know, once my third movie tanked at the box office, you know, it's back to pushing that giant boulder up the hill, it is never gotten easier. And the only reason to stick with it is because you don't have a choice is because you love this thing so much. You have to do it. Like if you want to do it for all the other reasons you think it's cool gig you want to be famous one that compiled or whatever those other reasons are, forget about it is too hard. It is too filled with disappointment and constant rejection that you know it if you're not in it, because you have no choice. You know, the movie Gods have called you and they said, Hey, man, this is what you're doing like it. Are you ready? That's the deal.

Alex Ferrari 37:51

No, do this. And I've tried to I've tried to quit. I've tried to quit this crazy a bunch of times, and I can't man I can't. I've tried. I've stepped out a bit for maybe a few years, but my foot was always back in it. I've literally tried to quit. It's like a bad drug manso hard. . Like you can't. You can't quit it because it's just something that is inside of us. Like you can't not be an artist. It's

Edward Burns 38:14

I look at all the films I've made. And I've made a couple that you know, really just like they didn't work in any way. Right? Yeah, critics didn't like couldn't sell them. When we finally sold them. It was one of those terrible deals you speak about in your book, you know the no advance partnership with the shady distribution company that doesn't

Alex Ferrari 38:34

Have a cigar and he's like, Hey, can just give me a poster.

Edward Burns 38:38

Here's the while making every one of those films I had a blast while you're on set working with these actors watching them. Bring your words to life. And on every single film I've done, I've met someone or work with someone who has become either a lifelong friend or a lifelong filmmaking partner. You know my director of photography guiding will RXR he and I are an absolute best friends. The first one we did together as a movie probably never even heard of looking for kitty. We did on a lark because we wanted to shoot on that new Panasonic with the the oscillating glass filter you did you did?

Alex Ferrari 39:19

Which one did you do? Not the Panasonic CVX did you shoot it? No, you shot it on the DVS. So you got the adapter. So you got you got the adapter to put it oh yeah, I've shot my first shot on the DVS I edited a Final Cut Pro four.

Edward Burns 39:31

And John loss had a company What the hell do they call that they would do what a bunch of movies with that camera, I think was it was a movie with Katie

Alex Ferrari 39:44

Holmes. Yeah, the pieces of April

Edward Burns 39:47

Pieces of April. That was sort of the biggest success of those. But that was shot on that camera and they were doing these movies for $250,000. They got a special agreement with the unions. So you can make a union film For 250 with that camera as long as you abide by certain things, so I heard that I was like, I'm all in, let's do it. And we quickly wrote a script. And we thought, we'll just hire our friends. We'll kind of improvise it. And the movie just I mean, it really just didn't work. But the great thing is, that's how we met well. So you know, even though it's tough, and it's brutal, filled with disappointment, it's always kind of fun.

Alex Ferrari 40:24

No, that's, that's what this whole journey is about, man. It's about those relationships. It's about those experiences. And I think a lot of filmmakers make that big mistake of the end game like the the, what is the endgame? Is it when the movie is finished? Is it when it gets old? Is it when it gets to a festival? Like, what is the moment where the end happens? And if you're only looking for the end, you're going to be disappointed constantly. But if you're enjoying the ride, then that's a career that's a life because you I mean, and that's something that I so admire about you and your career, is that you seem to be just having a good time.

Edward Burns 41:00

Connected to that. And that thing, you're speaking about the journey, you know, Aaron and I, we made this movie in 2012. Fitzgerald's family Christmas. Yeah. And what we did with that was the idea of it's kind of a long story, but I acted in this movie with Tyler Perry, who, obviously very successful,

Alex Ferrari 41:21

So he's done, okay, he's done, okay.

Edward Burns 41:23

He's the man. He's like, you know, those first two movies you made there were so successful. And then you never go back and do anything about Irish families again, what because because you got to super serve your niche to even to your point, he's like, I guarantee you the people that love those two movies would love another as an Irish family movie from you. And then you know, we can talk further, like, you know, think about an evergreen Tyler Christmas movie. That's something that every year you can kind of hopefully resell. So I kind of had this idea and I just made two other micro budget movies, I made a movie called Nice Guy Johnny for in the camp for 25 grand. That's a good story about why I made that movie that we made a movie on the Canon five d newlyweds got in the camp for 9000. So through those two films, speaking of like, movies, you know, kind of successful in the in the micro budget world, but my casts were great. And they found all these great young new actors in New York. So I was like, alright, so Fitzgerald's what I'm gonna do is I'm gonna bring my, my new family of cast members and marry them to my old family of cast members that I worked with Connie Britton, Mike McGlone, will replace the mom and needed Gillette. And so it was sort of like wearing the whole family of our all of our actors together and make this movie. So we make the movie for $250,000 all in, and I can get what festival we're trying to get into. Don't get in Aaron and I are devastated. And now we're waiting for Toronto. Everything is hanging on. If we get into Toronto, it's a whole new world for us, like, you know, to get back to that level of a prestigious festival. We get into Toronto, where high five and you know, we think it's going to be great. We go to Toronto, our screenings are great. But what doesn't happen is, you know, we don't sell the movie for millions of dollars. You know, we're not the Macmillan story of Toronto. We're another one of the movies that played at a big festival. And as we're getting on the plane to fly home to New York, as like, you remember the like the endless like weeks of anticipation, leading up to the we hear from Toronto, did we get in? Like anything different today than on that last day when we wrapped? Nothing? Not a single thing is different. So why do we get obsessed with the idea of, you know, getting into these festivals, it's great, and it's fun. But really, at the end of the day, the filmmaking experience was a blast. We worked with all of our friends, the outcome, really, I know, people say, Oh, that's bullshit. And I don't believe that, you know, you know, you don't look at your thing, you know, your reviews or care about the box office. I'm telling you after 26 years, it's nice when the good stuff comes. But we really don't. It's like we just know, a whatever happens, good or bad. Another 18 months from now, we'll have another script done. And we'll figure out how to make you know, we'll try and get 6 million to do it. If we can't do that and figure out the you know, $200,000 version of the movie.

Alex Ferrari 44:34

That and that's and that's only someone who's, who's got a couple of Gray's in their whiskey in their in their, in their in their beard that can say things like that. Trust me, I've got a couple of myself. So yeah, exactly the gray beards. But the thing is that but when you're 20 you can't You don't you don't grasp that yet. When you're when you're young, you just don't grasp because you just haven't been down the road yet. So I hope people who are in their 20s are listening to these two old farts talking I don't mean to speak for you, sir. But this old fart? Yes, you know these two old farts talking about the olden days. But there's a reason why. What is it? There's a saying and my wife's Colombian. And she has a saying a Spanish saying that says, The devil is more of the devil, not because he's the devil, but just because he's just been around for a long time. And it's it says something like that translates into that. And it's a it's so true. It's like you just know because you've just been around long. Now I have to ask you that when you jump from McMullen to she's the one that's a slight budget difference. And also a slight cost difference as far as the prestige of the actors you were dealing with, because I know Cameron, Cameron Diaz was in it. And obviously Jen and Jennifer Aniston was in it was Jen was just starting, was friends and friends was still a thing at that point, right or not yet.

Edward Burns 45:52

So yeah, it's funny, like nobody was a star yet. So Jennifer had, I think it was, it was after the first season of friends. Yeah. So you know, she's an actress on a sitcom. I read it the sitcoms very successful, but it isn't like, friends, you know, whoever would have been the big, you know, female movie star at that time. Right? You know, and she came in and auditioned and was great. And you know, I mean, like, and just crushed the part, Cameron was in the mask, right? You know, so again, no one, you know, Cameron Diaz wasn't a household name by by any stretch that she was,

Alex Ferrari 46:29

Oh, she's the girl from the Basque, right?

Edward Burns 46:31

She's the girl from events, you know, a couple of years later, Something About Mary different deal. But you know, it's interesting, like two actors who, you know, an actress who kind of was the runner up to Jennifer's part, and the actress who was sort of my second choice for Cameron's part. We ended up casting in the movie and that was Lesley men and Amanda Peet. Were also in that movie. So the real the the heavy hitter that we had at the time, like the actor to be intimidated by as a really, really first time director was John pony. Yeah. You know, and I knew John Mahoney from eight men out Moonstruck

Alex Ferrari 47:08

He's legend, legend, a legend. So how do you do so as a as a first quote unquote first time filmmaker, like in a professional environment? How do you handle dealing with the I mean, the I mean, obviously, you didn't have any giant movie stars that you were dealing with? You had professional actors, like seasoned professional actors, how was that adjustment from no money, over 12 months was shortened to now on a $3 million budget and a little bit more breathing room.

Edward Burns 47:34

That's it two things. One, the adjustment to working with the actors, I would say really wasn't much of an adjustment. Because nobody had a ton of experience. We were all the same age. You know, we're all just kids in our 20s doing it, you know what I mean? It wasn't like I was working with like, McNulty and you know, like a bunch of seasoned vets were like a bunch of kids making an indie movie in New York. So it was like, we're just hanging out and became friends. So there was no real intimidation factor. on set with the hackers, where I was truly intimidated was like walking onto set day one, we had a scene at the airport, JFK, you gotta have the terminal closed. I, you know, there's 150 people there that are my crew. Now, granted, I've met my department heads. We've been through pre production together, you know, I have good relationships with them. But when you you know, step onto the set and 150 people look at you and you're 27 years old, and they'll I got what's first up the like, okay,

Alex Ferrari 48:34

Here we here we go. When that when the dolt when the dolly grip has has shot probably 70 or 80 features. And they're looking at I had to believe when you walked in at 27 You know that some of these crew guys were like this son of a bitch. How did this guy get this? And did you get that vibe on some of this stuff?

Edward Burns 48:52

There was probably some of that, but it's funny. You mentioned that dolly grip was a top hog guy named

Alex Ferrari 48:58

Of course his name was off.

Edward Burns 49:02

We mean say two words to me for about the first two weeks, but eventually, you know, I think I want them over.

Alex Ferrari 49:09

You broke you broke them down and you broke them down. When I was that when I was that young directing on big sets, doing my commercials and stuff. I would the same thing you'd walk in these guys are just like, Who's this? Like, they have to smell you for the first like half day before like, Oh, this guy even know what he's doing.

Edward Burns 49:27

What the fun thing from that is. There was a PA on that film. Stuart Nikolai. And I'm so I'm 27 at the time, he's probably 23 It's his first gig in the film business out of college. And he works in the location department. Right now. He's been my location. main location scout on you know, I did a public did a TV show a couple years ago called public morals. Now bridge and tunnel. So you know again, back to the relationships thing, you know, He's a PA who's my age, we become friends. You know, I ended up you know, he worked on sidewalks in New York. So over time, you know, as he kind of moved up the road, he then became sort of my locations guy

Alex Ferrari 50:13

So and you never know who you're gonna meet along the way. Look at that, like the PA guy. I was talking to somebody the other day is like the PA on Nova Scott. Scott was Scott Moser was saying the PA on mall rats ended up getting him the job or introducing him to the job. That got him the Grinch when he just directed the Grinch the animated feature. And it was just because of that relationship. He was just cool. And they stuck. But if he would have been addicted back then that's it. There is no there's no game. Now, the one thing out of all of our all those contemporaries that you had in that time period in the 90s, I think and remind me if I'm wrong, you're the only one that became also a full fledged actor, as well was there I know, tintina pops in and out. But like, you know, you go off and act alone. And don't direct everything you act in. So you were one of those guys, you have a unique perspective on this. Because after she's the one, you worked on another little independent film called Saving Private Ryan, with an unknown director, Mr. Spielberg at the time, dude, what was that like, man? Like, just being on that show? And watching? I mean, the masterwork. Yeah. So

Edward Burns 51:27

I mean, as you can imagine, as a, so I, well, first up, it was like, for me, it was graduate film school. And I was very lucky, you know, when we were sort of, probably two days before shooting, we were doing sort of our, our show and tell and showing him what we look like in our uniforms, and how we handle the weapons and all that. I said, you know, I hope you don't mind, if we're shooting, if I could just, you know, kind of hang out, look over your shoulder, like any whatever you want to do. Like, just, you know, you're in this movie, you're welcome to, you know, stay on set all day long, if you want. So I took advantage of that, and, you know, used it as an opportunity to go to graduate film school. And it's funny, you know, you mentioned before, like, showing up on the set of she's the one and, and, you know, the the intimidation, and also working with actors. And I will say on that film, and and probably I did it on Nick Mullen, I'm sure as well, I thought the role of the director was to be directing the actors all the time. So after a take, I'd say cut. And then I thought I had to have some notes. And I told me, We tried doing it this way I tried, they went that way, or could you give me some of this and give me some of that, which they were, you know, we got a gang of us on that sample. That is, you know, five of us. And for almost two weeks, he goes action and cut. And that's it. And we do three takes and moving on we start thinking he hates us and thinks we're terrible. We're waiting for the new pages of the script to show up to discover that we're all gonna die long before we find you know, Matt Damon. And then finally, we have a day where he's like, caught, caught, caught caught, Eddie, come on over here. I need to try and do this. And you know, Adam, you know, to Adam Goldberg, you know, I just kind of feel like you're rushing through this, and then you slow it down. And so it gives us all these notes. And you know, at lunch that day, you know, of course, I'll tell him why do you think he gave us the notes today? So much we go over, we talked to Louise's, you know, we asked him, he said, we'll tell you to know what the hell you were doing. And he's like, look, I hire professionals, I assume that you've done your homework and that you show up in the morning prepared. So I'm not going to jump on you after your first take and sort of hurt your competence. By suddenly giving you a note, I assume it's going to take you three or four takes to find your way into it. Now some actors can get it on the first day and slowly fall apart. Because like I got on sambal here with some seeds or I got five guys, you know, all talk. I sit back and let you do it. And I'll let you figure it out. And you know, for two weeks you did until today. So today I stepped in. And that absolutely changed my approach with my next movie. I made Sidewalks of New York and I had a grant that I was doing I worked with Stanley Tucci and Dennis Farina and you know, Rosario Dawson, which is, you know, probably a second movie. Um, but on that bill, that's what I did. I was just like, I'm gonna sit back and let them show me what they've prepared. You know, and I can you know, you work with someone like Stanley you know, the first take he does it the way that it's scripted. The second take, he kind of plays with it a little bit, and then he sees the you're giving him room to play. And then he kind of really does was his thing. And you're like, Thank God, I did not step in early. And give him a note. Because now he feels so comfortable. And he's just giving me all of this great material. And that's the way it works. I very rarely give any direction now, unless an actor is sort of taking it off into a direction, that's completely well, you know, I mean, the big one I do, because, you know, I kind of do these talking New York movies is speed up the pace, you know, my New York actors kind of get the, the cadence of how I, I want the characters to speak. Sometimes other actors need to just speed it up a little bit.

Alex Ferrari 55:39

It was at the biggest lesson that you that the biggest lesson you learn watching him direct.

Edward Burns 55:45

Ah, then, I guess the second one was, if something that he has pre planned, doesn't work, he doesn't beat the dead horse. You know, like, we had a pretty complicated Steadicam shot when he was trying to link a bunch of us together. And he probably did it about four or five times. And I could tell him in yatish, the DP, they just weren't happy with it. And, you know, I mean, like, it's a big, it's a big thing. You know, this squibs going off and stuff. And he's like, yeah, just give me a minute, just give me a minute. And he kind of goes off, and he takes, you know, five or 10 minutes, is looking at the scene and he goes, Okay, scratch that we did, I got a new way to shoot. And we took a totally different approach into the scene. We did a scene with the dog tags, where we shot it as scripted before lunch. And it was another one of those scenes where he just is like, yeah, I don't like your system, not happy with it. Pull us all together to lunch. He goes, guys, do me a favor, just improvise something here. I just want you to rip for 20 minutes go through the dog tags. And, you know, the funny story is in doing that, I read off a bunch of dog tags. And I named a bunch of guys that I went to grammar school with. And they had you know, the I forget what writer was on set that day. But they recorded the improv and then from that, they rewrote the screen the that scene, and we shot sort of a new version of it after lunch. So a The good thing was I got to plug all my buddies names in the movie and it's still there, Mike says Ariel, Gary anaco, Vinnie Rubio, so they love that right.

Alex Ferrari 57:24

Can you imagine, like, you're sitting in the room, you're sitting there going,

Edward Burns 57:28

I didn't tell him so they're sitting in the theater. So, but anyhow, like that was a very valuable lesson to like, you know, in your gut, I'm sure you can speak to this as a filmmaker, you have to trust your gut, like know when it doesn't work and when it's not funny or adjusted, you know, it feels whatever your gut is telling you that and a lot of times you just you know, you're afraid to make that kind of change on set because you know, what's at stake right? It's money time. And seeing Steven with with a movie that big. That goes time to change we did not have you know, we we shot that movie, it was scheduled to shoot 66 days we wrapped in 58 That's how efficient the filmmaker his man. So you know, the other thing was, you know, we shot all handheld available light, sometimes two and three cameras go into it for a dialogue scene. So you know, the movie I make after that sidewalks in New York, not only did I steal the directing style, but that's how I came up with the pseudo doc style. I was like, he's shooting this like an independent movie, bang and through scenes here, because the cameras on you know, the the operator shoulder was shooting available light. People are overlapping dialogue. I was like, alright, that's my next indie movie. I'm doing a pseudo doc for that very reason.

Alex Ferrari 58:54

Yeah, and I checked my last one with this little duck. Honestly, watching all of your DVDs, because you are so generous with your commentaries, reading your book, which by the way, if anyone has not read, independent Ed, you got I read this thing front the cover to cover before I made my first features. And I list I literally went out bought every available DVD. If it had a commentary. I got I got the special edition Marlin and she's the one and you that whole style of like, just getting out and going to do it like newlyweds. I was just like, You know what? That's that I can do. I can go out and do that. Because as filmmakers you get like, especially if you you know, especially if you are a professional filmmaker who's maybe done commercials maybe worked in bigger budgets or worked in post and there's a there's kind of you get up your own ass in a way because you're like, oh, I need a read. I need an Alexa I need. I can't make this movie for less than 7 million. Like these are the kinds of things that you tell yourself and then when you bust out like newlyweds, you know, and you're like, wait a minute, I got that here. I can go do this to like, Screw it, let's let's go on build something. It was extremely inspirational man. And that's, and that's one of the big, big things about your career that I followed over the years man is that you have no need to go back and make a $9,000 movie, you have no need to go make a quarter million dollar movie, you don't need to do that you, you could have very comfortably kept acting, maybe get one, one movie every four or five years, that's four or 5 million or 6 million or something like that. Do some TV show, there's no need for you to go back and do Indies. But you keep going back. And that's that respect for the for the indie, that indie. You never left the indie roots, you go and play in the big budget stuff, no question. But you come back. And that's like, there's no other, I can't think of many other filmmakers of your, of your generation that does that. So man, thank you for keep doing that and inspiring us.

Edward Burns 1:00:53

When it goes back to H fun, right? I just like, you know, and you've done some bigger budget stuff. So you know, what it can be like sometimes to deal with, you know, and I have plenty of friends who work in the studio business, and they're great people, they're easy to work with. But it's a different process, you know, okay, talk about sort of the times when Aaron and I will sit down and be like, Okay, we are making movies here we want to do, we'll talk about our two lists of compromises. And the two lists of compromises, we work off of our sort of, Okay, we're gonna have to go ask someone for money, whether it's 1,000,002 million, 10 million, there are certain compromises that are going to come with that money a is, they will fully expect to have the say, in a lot of the decisions. You know, starting with title of the movie, some notes on the script, who you're going to cast, if you're going to ask someone for $5 million, or $10 million, whether it's a studio or some indie financing, they are absolutely going to give you a list of names that you need to cast from, in order to get that money. The other thing is, when you do get one of those actors, and you've got your $10 million, the good news is, you're gonna have a much easier time selling that movie. And you've got a big bold face name on your, on your poster, which is going to excite the folks at Netflix or wherever, right? So that's one set of compromises the other set of compromises other ones, though, it's like, Okay, we're gonna make a movie for $25,000. And, you know, here are the compromises, we know we're going to have to make, we're not going to get a star, we're good. We're not going to get all the locations we want, we're going to have to be down and dirty odds are, we're not going to make any money, you know, our fees are going to be sort of coming on the back end if the movies successful. And we know it's gonna be almost impossible to sell. So what do we want to do this year? You know, like, do we actually want to go make a movie, which is the $25,000 version? Or do we want to spend the next two to three years trying to get that big name to Trump as a just trying to get the money, then trying to get the actor and then trying to get that movie up and running. And that is never a six month process? That is never a 12 month long process? That is several years of your life.

Alex Ferrari 1:03:28

And that's the one thing I want people to understand. Because a lot of people look at you like, oh, it's Ed burns, he could just call up a buddy of his that he's worked with and just like, hey, can you Tom, Tom Hanks, can you come by and do my 25 thoughts. And they just think that you can because you're in the system and you've been in the system, you've had success, that you can just make things happen. And the more I talk to filmmakers in this space, Oscar winners, and so it's the same story for all of them, other than Mr. Spielberg. And even then he had to go to India to get money for Lincoln. Like it still was a challenge for him. Everyone filmmakers still have to trouble still have all the same problems, different levels, but still the same thing.

Edward Burns 1:04:09

It's I mean, it just is never easy. I know Look, if you're making a certain type of film. I don't want to say that that's easier. But you know, there are certain films that you know that I'd say are more obviously commercial. You know, I was a kid when I'm in film school, you know, I'm full I am not the guy who was falling in love with Star Wars and wanting to go make those kinds of films. I did not love action films. You know, I mean, I loved Last Picture Show and tender mercies in Holland and I wanted to make you know, small little dramas or I loved you know, films like The Graduate The World According to Garp, and like I said to pho Woody Allen or to make you know, talking comedy dramas. Mothers, you know that that the market place for those films has all but disappeared. So, you know, I, you know, I if I wanted to call Tom Hanks, you know it would probably I'd have a much easier time getting him if I had a sort of big budget idea movie as opposed to one of my talking right

Alex Ferrari 1:05:19

So you packaging together a bigger movie will probably be a little easier for you but yet there's still hurdles and things you're gonna have to

Edward Burns 1:05:25

Scheduling years and you know a lot of your good friends, you know, people you've worked with, you've got a relationship with it still takes, you know, we're big movie stars, and they still don't get back to you for six months, you know, especially like, because you're trying to get them attached to raise your money,

Alex Ferrari 1:05:41

Right?\! You're never gonna go into

Edward Burns 1:05:44

A $6 million offer here. Like forget about Burns's script, right? Go to work.

Alex Ferrari 1:05:49

Right, exactly. Then you still gotta jump through those hoops. And they're scheduling issues in those agencies. Like, look, I know, Eddie, it's doing his thing. But there's 6 million bones right here. Let's go. Let's go. He's the he's still trying to find his money. And that's the thing. I want filmmakers to understand that there is no magic key, there's no, there's no end of the rainbow that we all still have to deal with that even at the level that you're dealing with. And the kind of success that you've had in your life and your career. You like when you just said that? You're like, yeah, that screws, bird. Chris burns his script, I got $6 million. Right here, go with this. I see in those conversations. I've been part of those conversations and agents really like yes, some of them. Like, it's so hard. I mean, unless they're like your wife, or your brother. And even then they're like, Look, man, I love you and all but I got $10 million to go through this other movie. Right?

Edward Burns 1:06:38

Yeah. And look, you know, I mean, plenty of actors will do it. But typically, it is, you know, their passion project, right? Where they're gonna go cut their fee to go do something a lot of times and you know, as well, they should, you know, it's like, they don't necessarily want to help you make your passion project. They've got that script they've been sitting on for years, and they're slowly putting it together and trying to get the financing together. So.

Alex Ferrari 1:07:04

So it's something that you talk about in your book, which is Brothers McMullen. 2.0. Can you break down what brothers meant bond 2.0? Because it's something that I used extensively in my last two features.

Edward Burns 1:07:17

Okay. So yeah, so, you know, I, I'll back up a little bit, because it's kind of interesting how my career kind of has panned out, right. So I use for my first four films, you know, it's with Moe, and she's the one movie called no looking back, which really didn't do well on Sidewalks of New York. They all did, you know, pretty well. And I credit that to the fact that I'm still a kid, a screenwriter, who believed in outlining before he wrote his scripts, I still am a student of the game. I am not so arrogant to think that I don't need to go back and kind of you know, play within a three act structure. And really kind of have a an outline that's, that's airtight before I sit down to write right? After that. I decide for whatever reason, you know, whether it's laziness or arrogance, I stop outline. And then I make four movies I make these before you probably never had or maybe you have most people on Wednesday looking for kitty, the groomsmen and Purple Violets, right? All four movies get terrible refuse. All four movies don't work at the box office. And then after that, I am in directors jail, like I really I have my next script. And for about two years, I can't get it financed. I'm having a very tough time getting actors attached. You know, at first, we were looking for 8 million than six to four than two that were down to like 1.2. And Aaron and I have a meeting in the Hollywood Hills, some guy's house and again, you know, you joke about the gallery. So guys stick around inside those deals. And still, they're kind of telling me how I need to make this movie. And and I go back to the hotel, I'm staying in LA and we have a drink at the bar. And I'm like, moving. It's over, man. Like how did this happen? Like, you know, it wasn't that long ago, I was the guy who led both Macmillan. And now we're up here and this guy's telling us we got to rewrite the script based on his notes or million dollars. I said it's over man, we are in directors jail. And over those beers were kind of joked around like, how is it that when I was 24, I was able to write the Brothers McMullen and with no connections and no money. And I didn't know how to make movies. I was able to make a movie that was you know, still to this day, my most financially successful film. I was like, or that he was like, why don't we just do that again. So there on the napkin at the bar, we came up with Macmillan 2.0, which was basically the rule We're how we made McMullen and we wouldn't divert from that. So $25,000 to get into the can 12 days of shooting, three man crew, all unknown actors, all actors had to bring their own wardrobe, how to do their own hair and makeup. And every location we had to get for free. All right, so that was basically, those were the rules. And the next day, we sat down, and we started and we said, we have to do an outline.

Alex Ferrari 1:10:34

So you learned, you learned a little bit the last four movies.

Edward Burns 1:10:38

And, you know, um, we, we both loved the graduate. And, you know, I remember we were talking about the movie Sideways, which we both loved. We're like, alright, let's just, it'll be two guys. Let's just start with two guys. And we just started riffing and overtime and turned into a kid and his uncle instead of two best friends. But, you know, and that's why I think for people, like if they don't know what to write, or they kinda have an idea, but they need, you know, sometimes it's okay to go look at one of your favorite films, and almost start to tell your story within the framework of their story. Right? Like you could look at, you know, I know, let's say I'm Brothers McMullen, I, at a certain point, when I was hitting the wall, I looked at Hannah and Her Sisters, and I was like, oh, okay, I see what he's doing here. He's kind of weaving those three stories together, and then they come together, it seems to be every 15 pages in the script. Alright, so let me I gotta cut and paste this scene and move it there. So that's a very valuable tool, I think, if you're a young screenwriter, because, you know, even if you rip off the structure of your favorite film, for your first draft, you're going to do you should do you know, 2025 drafts of your script, by the time you do those 25 drafts, you know, it would be unrecognizable, if you're if you're playing with some structured stuff. So anyhow. What was it? Oh, so that's what we did. We just started outlining and, you know, grip maybe in six months. And then so let's go do it.

Alex Ferrari 1:12:19

And then use it was the first one and 2.0 Was that nice guy, Johnny? That was nice guy, John. Yep. And that was 25 grand. And then that did well, right. That actually,

Edward Burns 1:12:28

Well, we do. You know, the other thing that happened was the movie that I spoke about that didn't do well, purple violence, right? That was a movie was actually okay, that movie we couldn't get. We were offered a couple of distribution offers. But again, like your book talks about it was really bad deals, you know, there was no chance that our investor was going to get any of her money back if we went with that. And it would be your typical New York LA, one screen. If we do decent, maybe they'll give us a few other markets. But we can see the writing on the wall. At that time. iTunes had just launched. They had the music for a couple years, but they just want the movie sort of page of it. And I was starting to watch a lot of movies on iTunes. So I was like, Alright, why don't we go to iTunes? And what maybe they'll release us as their first all exclusive feature film. And because it was a new, basically a new bit of business of them of theirs. They said Yeah, so purple was was the first movie ever released exclusively on items

Alex Ferrari 1:13:37

For transactional for transactional for a transaction. Yeah. And it did great. You know,

Edward Burns 1:13:42

I mean, it didn't do it didn't make its money back. But like we saw with those numbers were, and we're like, okay, so we make a movie for $25,000. All in 125. We post based on what Purple Violets did, we know we're going to, you know, we're gonna make some real money here. So that was the plan and it did.

Alex Ferrari 1:14:02

So So for everyone listening to the What year was this?

Edward Burns 1:14:05

This is 2009 to 2010 is when it comes out.

Alex Ferrari 1:14:10

Okay, so that's why it is does not exist anymore. So everyone listening like I'm gonna do what Ed Burns did like nope, no t VOD for independent films is essentially dead unless you can drive traffic. The the finding you on iTunes thing is gone.

Edward Burns 1:14:27

Even at that time, we think about we're basically you know, we have an aggregate aggregator distributing that title, but because, you know, we're really the first one sort of embracing iTunes we're getting a banner on the landing page and when you go to iTunes it was like nice guy Johnny. And we were we ended up being the number fourth most rented title from one of the months and it was our hurdle

Alex Ferrari 1:14:50

So nice guy Johnny did very well done.

Edward Burns 1:14:51

Nice guy John did very well. Yeah, right. And then did as well.

Alex Ferrari 1:14:55

And right and then you did you did you did a movie called newlyweds which was 9000 which was, you know, when I saw that I was just like, wow, this is it's an apartment, it's on the street. He's stealing all the locations. You know, it's just like, yes. Yes, yes. And it just and that one did extremely well as well.

Edward Burns 1:15:16

Right. Yep. So that we know we finished Johnny, we had a blast doing it. And then we, you know, we turned it around real quickly. And we saw that it was it was working. I had just read an article about people who are shooting commercials on the five d. So, literally that day, I jump on the train. I go up to b&h on 34th Street, I buy the five D, I call my DP will I say, Look, I just bought this five d saw this thing? Why don't we shoot a scene tomorrow to see if this thing works. So I had kind of an idea of something I wanted to do. I quickly wrote a scene I called my buddy who owns a gym. I was like, we need to come over to your gym. I'll be there for an hour. And we basically I said, I'll play this personal trader, and we'll shoot one half of a phone conversation as just a camera test. And that scene is in the moment.

Alex Ferrari 1:16:12

Of course it is. You never would never waste not what not?

Edward Burns 1:16:16

Well, when we dumped it into, you know, my desktop computer after we shot like that, we crap that looks good. Okay, let's do it. So I just started writing that.

Alex Ferrari 1:16:28